An old athletics coach of mine once told me, “if you don’t have time to warm up, you don’t have time to work out,” and this is a rule I’ve lived by ever since. A thorough warm-up can make your workout more productive and may even reduce your risk of injuries.

It’s time well spent!

However, a lot of people are confused about the best way to prepare their bodies for training and end up wasting their valuable time on ineffective methods. Worse still, some even skip warming up entirely.

In this article, we reveal the best preparatory methods to use before strength training and explain how to design your own bespoke warm-up routines.

Why Warm Up, Anyway?

Some people think that warming up is a waste of time. That’s probably because they don’t understand the purpose and benefits of warming up. So, let’s fill in the blanks in your warm-up knowledge and discuss how warming up affects your body.

More energy

Your body contains cells called mitochondria which are responsible for producing energy. These cells tick along quite happily, keeping you supplied with what you need to function correctly.

However, when you start training, these cells can be slow to respond, and the energy demand outpaces the energy supply. As such, you may feel out of breath, and your muscles may even feel weaker than usual at the start of your workout.

Needless to say, this is NOT a great way to start your training.

Warming up increases the energy demand gradually, so your mitochondria get a chance to upregulate energy production. In simpler terms, your warm-up provides the bridge between being sedentary and being active, so training is less of a shock to your system.

The result is a more comfortable start to your workout.

Improved blood flow and raised muscle temperature

Blood flow tends to be quite slow when you are at rest. Your heart and breathing rate are low, and your blood vessels are constricted. This limits the blood flow and oxygen supply to your muscles. But, when you start exercising, the demand for oxygen increases dramatically. It takes a few minutes for your body to match supply with this raised demand.

Warming up raises your heart and breathing rate, opens up your blood vessels, and increases oxygen saturation in your muscles, so they can function more efficiently.

Increased blood flow also raises the temperature in your muscles and your core. Muscles stretch and contract more efficiently when they are warm.

More mobile joints

A joint is where two or more bones come together to form a union. Some joints are immovable, such as those in your skull, while others are semi-movable, like your spine. However, many of your joints are freely movable and involved in the exercises you’re about to do.

Freely moveable joints are lubricated with a substance called synovial fluid. This is an oil-like substance that is produced on demand. Being sedentary means that synovial fluid production is low, so many people have dry, unlubricated joints. Training on dry joints can cause excess wear and tear and limit the range of motion.

Warming up increases synovial fluid production, ensuring your joints can move freely and with less potential for wear and tear. If you have pre-existing joint issues, e.g., osteoarthritis, you should find your symptoms decrease as you warm up.

Increased muscle elasticity

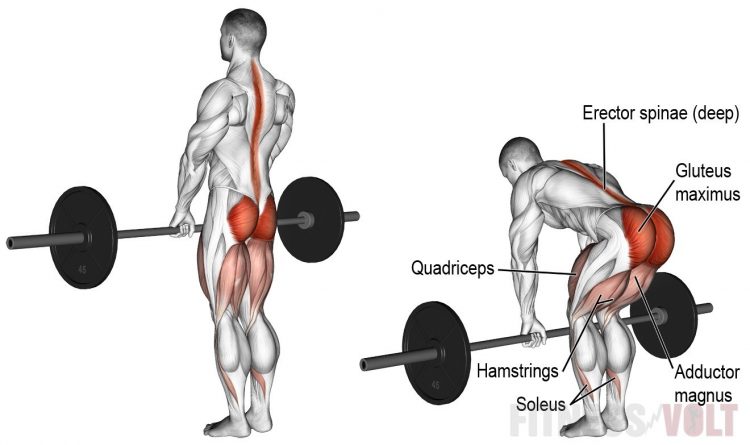

Warm muscles stretch more readily than cold muscles. A lot of strength training exercises require a large range of motion, e.g., dumbbell flies, lunges, deep squats, Romanian deadlifts, etc.

Being sedentary, e.g., sitting for long periods, causes muscles to shorten. Even if you have good flexibility, your muscles may still feel tight after long periods of inactivity.

While your muscles will become more flexible as your workout progresses, if you want your first few sets to be as productive as possible, it makes sense to maximize muscle elasticity BEFORE you start lifting.

Greater strength

Your muscles are controlled by your central nervous system. Regardless of how big your muscles are, their ability to produce force is dependent on how well your nervous system can activate them.

Warming up helps get the nerve impulses responsible for innervating (turning on) your muscles flowing faster and more powerfully. That’s why you feel stronger as your workout progresses and why weights you can usually lift comfortably feel heavier at the start.

Bringing your muscles “online” before lifting will ensure your first few sets are as productive as possible. You’ll also feel stronger, which is a positive way to start any workout.

Creating a better mindset

Training is as mental as it is physical. A good workout starts with the right mindset. If you aren’t concentrating, not feeling very enthusiastic, or just “aren’t into it,” your training is bound to suffer.

Warming up your body gives you a chance to dial in your mind on what you are about to do. You can use this time to mentally rehearse your workout, get fired up, and shift your focus away from your life outside the gym to what you need to do to achieve your fitness goals.

Do not underestimate the power of the right mindset for getting a good workout; where your mind leads, your body follows!

You MAY experience fewer injuries

Oddly enough, the main reason that many people warm-up is not actually a proven benefit. After all, injuries happen to people who have warmed up, too! Studies are inconclusive, with some determining that warm-ups do lessen the chance of injury. In contrast, others found no statistical differences (1).

Being injured can interrupt your training for weeks or even months, so if warming up COULD reduce the risk of injury, the small investment of time is worth the potential payoff. However, it’s impossible to say that warming up will prevent injuries. Sometimes, injuries just happen, regardless of how thoroughly you prepare your muscles and joints.

How to Warm up for Strength Training

Warm-ups are like workouts – they vary a lot, and there are several ways to achieve the same outcomes. Because of this, there is no single best way to warm up, as your personal circumstances and the training you are about to do determine what type of warm-up you need to do.

That said, there are several methods you can use to prepare your body and mind for your coming training session, and we’ve listed them roughly in order below. However, don’t feel you need to use all of these methods, as some may not be appropriate to your needs.

Pulse raiser

This is the part of your warm-up that gets you warm. Typically, this warm-up component involves 5-10 minutes of progressive cardio. By progressive, we mean it starts easy and gets a little harder over time, e.g., walk, jog, run.

The best options for the pulse raiser are full body cardio exercises such as the rower, air-bike, or elliptical. However, for lower body workouts, bikes and steppers will suffice.

Take care not to turn your pulse raiser into a full-blown cardio workout. Instead, save your energy for lifting weights and only do the minimum to achieve the desired results. By the end, you should feel slightly out of breath and may even be sweating lightly. However, you should not feel tired.

Not everyone needs to do a pulse raiser. For example, if it’s a warm day, you may already feel warm enough. You probably won’t need a pulse raiser if you have been active during the lead-up to your workout, e.g., you walked to the gym.

But, if you feel cold or sluggish, a pulse raiser may be very valuable.

Dynamic stretches

Now you are generally warm, it’s time to start preparing your muscles with stretching. However, when it comes to flexibility training, most people tend to think of static stretches, where you hold a position for an extended period.

While static stretches can be beneficial, they make your muscles relax, so they are not really suitable for warming up and are best left for the cooldown.

The best type of stretches for warm-ups are dynamic stretches.

Dynamic stretches involve moving into and out of a stretched position without stopping. They’re done for reps (usually about 10-15) and not held for time. Examples of dynamic stretches include:

- Forward leg swings

- Cross-body leg swings

- High knee marches

- Waist twists and side bends

- Standing chest fly

- Standing overhead press

Each movement should be done smoothly, not too quickly, and using a progressively larger range of motion. Dynamic stretches should not be confused with ballistic stretches, which are done much faster and with more momentum.

There is no need to dynamically stretch all your muscles. Instead, focus on those you are about to train.

Joint mobility

Now your muscles are feeling warm and supple, it’s time to move onto your joints. Joint mobility exercises are simply movements that take your joints through a progressively wider range of motion. This maximizes synovial fluid production so your joints move more freely.

With all joint mobility exercises, you should start small and increase the size of your movements over 10-15 reps. Examples include:

- Shallow progressing to deeper squats and lunges

- Cat/cows

- Wrist circles

- Waist twists

- Arm circles – forward and backward

Ideally, your joint mobility exercises should be similar to the exercises you are about to do in your workouts, albeit done with no weight and with a progressively bigger range of motion. So, if your training includes squats and lunges, those movement patterns should feature in your warm-up.

Some dynamic stretches are also joint mobility exercises, so don’t worry if you feel like you are repeating yourself. Just do the chosen exercise once, and be happy it’s a warm-up twofer!

[sc name=”style-blue-box” ]

Check out the DeFranco 8 and the Fitness Volt five-minute mobility workout for more ideas on dynamic stretches and mobility exercises.

[/sc]

Muscle activation

A muscle is only as strong as your ability to switch it on. After being sedentary, your muscles are kinda sleepy, so you need to wake them up. That way, when it’s time to do your first set, they’ll be firing fully and able to produce the maximum amount of force.

One way to do this is with ramped sets.

Ramped sets are simply build-up sets that get your muscles ready for lifting heavier loads. For example, imagine your workout calls for five sets of five reps with 225 pounds.

Instead of jumping straight into 225, you ramp up to that working weight like this:

- 10 reps 45 pounds (empty barbell)

- 7 reps 85 pounds

- 5 reps 135 pounds

- 3 reps 175 pounds

- 1 rep 200 pounds

- 5 reps 225 pounds (1stwork set)

Note how the reps decrease as the weight increases. This allows you to improve muscle activation without accumulating unnecessary fatigue. Do NOT turn your warm-up into a workout!

You don’t need to ramp up for every exercise in your workout. Instead, you may only need to do this for the first 1-2 movements. Also, the heavier you train, the more ramp sets you’ll need. For example, if your first exercise is lat pulldowns with 140 pounds, one or two ramped sets should be sufficient.

Another way to increase muscle activation is with overcoming isometric exercises. With overcoming isometrics, you contract your muscles against an immovable object, such as a wall, yoga strap, or opposing limb.

Simply engage your muscles at about 75% of your strength and hold for 5-10 seconds, ensuring you can feel the target muscles contracting. 2-3 sets should be sufficient. Then, when you move to the exercises in your workouts, you should feel your muscles firing more efficiently and have a stronger mind-muscle connection.

This method is ideal for workouts where you’ll be working with higher reps and lower weights, e.g., 8 to 12-rep bodybuilding-style workouts.

Here are a few examples of overcoming isometric warm-up exercises for the legs, chest, and upper back:

Legs

Chest

Back

How Long Does My Warm-Up Need to Be?

This is a hard question to answer because there are several factors that determine how long it’ll take to prepare your body for your workout.

Considerations include:

Workout intensity – the harder you are about to train, the more warming up you’ll probably need. For example, if you are working up to a new bench press 1RM, a longer warm-up could help you lift more weight. But, if you are doing a high-rep/low load HIIT workout, a long warm-up will be a waste of your valuable time and energy.

Previous levels of activity – sedentary people probably need longer warm-ups than those that are habitually active, e.g., office workouts vs. manual laborers.

Age – older joints and muscles tend to take longer to warm up than those of a younger person. Therefore, the older you are, the longer your warm-up needs to be.

Previous/current injuries, aches, and pains – if you have old or existing injuries or aches, you may benefit from a longer, more comprehensive warm-up. Increasing tissue temperature, blood flow, and synovial fluid production can help ease chronic aches and pains.

Environment – if you are cold or are working out in a cold climate, you will probably benefit from a longer warm-up. Conversely, if it’s hot, you may not need to warm up for as long.

[sc name=”style-blue-box2″ ]

A warm-up should last between 5 to 20 minutes, depending on your needs. So long as you feel ready to train by the time you finish, your warm-up has done its job, regardless of how long it was.

You only need to warm up for as long as it takes to get the job done. Do not spend more time on it than you need to. Remember, your warm-up is just the bridge that takes you from being inactive to your workout, so save your energy and time for what really matters.

[/sc]

Wrapping Up

A good warm-up can be time-consuming. However, it’s time well spent. Warming up can make your workouts more productive and may help you avoid injuries. Both of these things will actually save you time in the long run.

Tailor your warm-up to match the workout you are about to do. Your energy and time are valuable, so don’t waste them on warm-up methods that won’t benefit you.

Instead, make sure your warm-up matches the demands of your workout by selecting the most appropriate methods.

Finally, even if you are short of time, don’t be tempted to skip your warm-up. It’s better to cut your workout short by ten minutes than fail to prepare your muscles and joints for what you are about to do.

References:

1. PubMed: Does warming up prevent injury in sport? The evidence from randomized controlled trials https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16679062/